It is the sad paradox of wildlife conservation that as soon as a species seems to make progress toward recovery from near extirpation, some people rally to be permitted to hunt and trap them again. This is exactly what’s happening in Indiana right now with the state’s only remaining native wildcat, the bobcat.

Earlier this year, a small but powerful group of recreational fur trappers helped push a bill through the state legislature that forces the Indiana Department of Natural Resources to establish a bobcat-trapping season by July 2025. And last week, the Indiana Department of Natural Resources proposed that trappers be allowed to kill 250 of them using horrific methods including strangling neck snares and steel-jawed leghold traps, even though these small wildcats are only starting to return to their native habitats in Indiana’s woods. But there is hope: concerned residents of the state still have time to prevent even one bobcat from being killed.

The new law mandating a bobcat season allows the Department of Natural Resources flexibility in setting the quota of bobcats that can be legally killed—the agency can even set this number as low as zero.

The Natural Resources Commission will take public comments into account before making its final decision, and they can still decide to set the quota to zero. For that to happen, though, the Commission needs to hear from Indiana residents now. The public comment period for Indiana residents is open and can be accessed by clicking “Submit Comment Here” under Bobcat Amendments at NRC: Rulemaking Docket.

This is not the first time that hunting and trapping groups in Indiana have tried to force the hand of the state to allow the killing of bobcats, but wildlife advocates have always managed to resoundingly defeat these misguided proposals. We celebrated a win in 2018, after a proposal to open a bobcat season was completely withdrawn by the Department due to overwhelming public opposition that we mobilized with strong allies in the state. A bill to open a bobcat season similarly failed in 2019.

Unfortunately, Senate Bill 241 passed in March 2024. Bobcat sightings on trail cameras, were touted as being justification for a bobcat season; misinformation and fearmongering abounded. One proponent claimed that simply seeing a bobcat meant that there were too many, and others stated that bobcats were eating too many turkeys, despite research by the Department of Natural Resources that did not document any consumption of turkeys by bobcats.

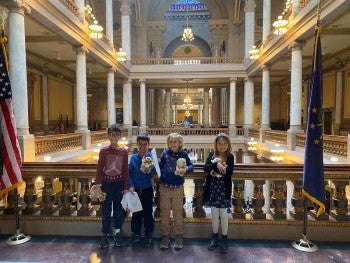

Powerful hunting and trapping groups lobbied hard for the bill, but Indiana residents who care about wildlife showed up in force, too. In a particularly inspiring move, students from Bloomington Montessori School traveled to the capitol to visit their state representative, respectfully telling him that they value bobcats and don’t want to see them trapped and killed. These young advocates were able to change his vote. Sadly, though, SB 241 became law despite their efforts.

Anne Sterling /The HSUS

There are many reasons to oppose the bobcat-trapping season. The proposal allows the use of cable neck snares, which are intended to strangle an animal to death by slowly cutting off their air supply, leading to hours or days of suffering. These snares can also catch animals by their torsos or feet, and the cable can become deeply embedded in their skin. Snares hung on a bush or tree can be difficult for people out walking their dogs to spot. This is why snares have come to be referred to as “silent killers” of dogs; unable to cry out for help, dogs may hunker down and pass out before slowly and quietly suffocating to death without their owners being able to rescue them. And snares frequently catch nontarget wildlife such as eagles and deer fawns, as well.

The proposal would also allow the use of steel-jawed leghold traps, contraptions that trappers bury underground and that snap shut when an animal steps on them. Like snares, leghold traps don’t discriminate, jeopardizing wild and domestic animals alike. They can cut through skin causing lacerations, and animals can damage their teeth and gums as they desperately try to free themselves. Trappers are permitted to leave traps unattended for hours; an animal caught in a leghold trap can be left to struggle for up to 24 hours, without access to water, shelter or food, until the trapper arrives to kill them by bludgeoning, strangling suffocation or shooting.

Very few Hoosiers trap (less than 0.06%). Those who do largely “enjoy” the activity as a recreational hobby or to score animal trophies. Only some of that 0.06% sell the fur skinned from trapped animals overseas in the fur markets of Europe, China or Russia. But the fur market is declining in the U.S. and worldwide as consumers demand that retailers stop selling it, and designers all over the world increasingly reject using animal fur in their products.

Hunting, trapping and habitat loss nearly wiped out bobcats in Indiana. In the mid-1900s, the species was listed as endangered under state law, and bobcats retained this status until 2005. The protections from hunting and trapping that come with endangered species status allowed bobcats to slowly begin to recover, making their way back to landscapes that were missing the ecologically essential little carnivores.

Most Hoosiers celebrate the return of Indiana’s only remaining native cat. Shy and elusive, bobcats are essential members of North American ecosystems who contribute to overall biodiversity and ecosystem health. Their diet consists mainly of rodents, rabbits, and squirrels, and they help clean up carcasses, helping to recycle nutrients back into soils. They can even help mitigate zoonotic diseases and chronic wasting disease. Kittens, who are playful and curious, depend on their mothers until they are about a year old. Bobcats even purr! Conflicts with bobcats and people are very rare, but Indiana residents who experience conflicts can legally obtain a permit to kill the bobcat.

In addition to submitting written comments in the coming months, the public can address the Natural Resources Commission and the Department of Natural Resources directly. A public hearing is currently scheduled for November 14, at 5 pm EST at the Southeast-Purdue Agricultural Center in Butlerville (4425 East 350 North). It will also be livestreamed here. It is essential that Indiana animal advocates make their voices heard for bobcats. Trapping is cruel, and the only justifiable number of bobcats trapped and killed in Indiana is zero.

Follow Kitty Block @HSUSKittyBlock.