To experience the natural world, we often navigate congested highways to swim in the sea, fly over patchworked terrain to hike through preserved forests and climb distant mountaintops to catch rare views.

Largely because of our ever-increasing mobility, the areas nearest to us are rarely the dearest—and all too easy to dismiss as familiar ground.

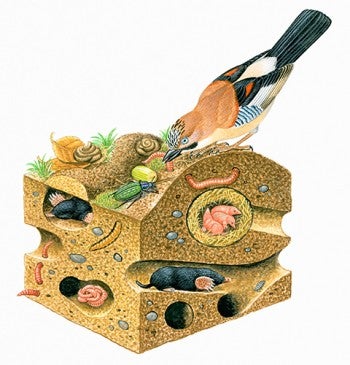

But how familiar are we, really, with what lies below, let alone who eats, sleeps and breeds there? Instead of traveling afar for a sense of place in the universe, what if we paid more attention to what’s right underfoot?

These questions are especially visceral once you’ve seen the seemingly solid earth shift next to you. More than once, I’ve been lost in thought in the garden when—in a flash so quick I question my eyes—the soil erupts into a tunnel just beneath the surface.

Meredith Lee/Humane World for Animals

Create a haven for wildlife

A humane backyard is a natural habitat offering wildlife plenty of food, water and cover, plus a safe place to live free from pesticides, chemicals, free-roaming pets, inhumane practices and other threats. And it's so easy to build!

Brutal treatment of moles derives from a British obsession with unnaturally pristine lawns on royal estates. Adopted here with near-religious fervor, the attitude causes suffering for species whose habitats foil the artifice of turfgrass. In the U.S., gardeners have harassed the humble mole with things such as chemicals, broken glass and even gum. And moles are the target of so many games and jokes that violence toward them is still socially acceptable; a friend’s cousin posted a Facebook photo of a mole she’d stomped to death, much to the mirth of her followers.

Advice on killing moles is easier to come by than facts about their valuable role. As Atkinson notes, about six papers on moles are published annually, compared with thousands on primates. “These animals have been studied from the point of view of ‘Let’s get rid of them,’” says HSUS senior scientist John Hadidian, “so their natural history is a lot more obscure.”

Out of the scant research, however, has come information that should impress even the cynics: Not only do moles aerate our soil and dine on invasive Japanese beetle grubs, but they’re considered “ecosystem engineers” whose kicked-up dirt can create fertile ground for plants that host rare butterfly larvae. Molehill soil is also beneficial to savvy gardeners, who make use of it in pots and beds.

Though I’ve never experienced mole damage, humane solutions exist for homeowners who do. If moles are entering gardens, fencing grounded with L-shaped footers can be placed around the perimeter. And molehills can be harmlessly shoveled away.

The best approach is to understand who really inhabits our properties and to appreciate the miracle of their existence. Years ago when I came across the decapitated trunk and nibbled roots of a rosebush, I made the common mistake of assuming a mole had been munching. But my new guest was a plant-eating vole, who shares few traits with moles save their similar names. And as I would soon learn from my favorite book on backyard wildlife, Wild Neighbors (written by HSUS experts), the only animal I had to blame was myself. By piling on too much mulch, I had issued a gilded dinner invitation.

Instead of asking my backyard friends to amend their ways, I changed my own, thinning the mulch while admiring the vole’s beaver-like precision in honing my rosebush trunk to a spear. Within a year, the roots regenerated into a bush now taller than I am.

Elsewhere on the property, moles still tunnel, but the only evidence of their presence is a sponginess where the earth softens underfoot—a reminder that life is everywhere, growing and changing in the places we most tread but least often see.