At Humane World for Animals, we work to protect wild species of many kinds from trophy hunting and lethal predator control programs. Bears stand at the center of this campaign, as the targeting of black bears by trophy hunters in the U.S. has increased in recent years, and there is an ongoing fight over whether grizzly bears should maintain federal Endangered Species Act protections. Here, Wendy Keefover, senior strategist of native carnivore protection at Humane World for Animals, discusses her love for bears and the many reasons we should come together to protect these animals.

A few years ago, in springtime, my partner and I were visiting Yellowstone National Park when we ventured into a semi-remote area where the road had been closed off to vehicles. There we found a group of photographers with camera lenses as long as telescopes pointing in the distance. When we looked in that direction, we saw a mother black bear and her two playful yearling cubs.

As we watched them interact, three hours passed. We were enthralled. The rambunctious, playful cubs ran and nipped at each other and their mother at one moment, and the next they were sprinting up a tree, grabbing the bark with their claws. Then, in a moment of tenderness, they were nursing, and when they were full, they nestled into a snuggly interconnected ball. It was magical.

Those moments made me realize something: Bears are infinitely patient, devoted and vigilant mothers—traits that many people may not associate with these animals. Typically, black bear mothers wean their cubs at around 9 months, but I learned later from a park biologist that those yearling cubs were underweight and so their mother was nursing them for longer than usual—these cubs were likely about 20 months old. I already knew that bear mothers spend prolonged periods raising and nurturing young and that bear cubs learn foraging styles from their mothers. But seeing those interactions in person brought this knowledge home to me in a new way. My emotional connection to bears and to our efforts to protect them deepened after seeing how devoted this mother bear was to her family.

There are so many reasons to care about bears and their protection. For one thing, bears are very intelligent. Ethologists, the biologists who study animal behavior, have produced various studies about bears’ intelligence that show that bears can count and assess their environment—just like a human. Bears use sticks and rocks as tools, particularly for grooming or scratching themselves in water. They fashion these tools by biting and shaping them. Bears have a right-paw bias while foraging; ethologists surmise that being right- or left-handed allows the brain to divide tasks between the two sides, allowing for greater cognition. Some have compared bear intelligence to that of great apes.

Bears are valuable members of their ecosystem communities. Grizzly bears and black bears, as they eat fruits, deposit pits and seeds across vast distances and disperse even more seeds than birds. Their large size means that they shift the environment just by moving around, creating breaks in the tree canopy that allows sunlight to reach the forest floor, which, in turn, fosters greater biological diversity. Bears break logs while grubbing, which helps the decomposition process and facilitates the return of nutrients to the soil. In one study, researchers found that black bears were the dominant species moving salmon from streams into riparian zones, which is land that borders bodies of water. The remains of salmon that bears leave on the ground help enhance tree growth. And when black bears are out of the den, coyotes and bobcats avoid the area, which indirectly protects gray foxes.

The chance of catching a glimpse of a bear is also a huge draw for tourism to parks, which helps to drive up the economy in the U.S. and Canada. From Yellowstone to the Great Bear Rainforest to Katmai National Park, wildlife watchers greatly outspend bear trophy hunters in all these regions.

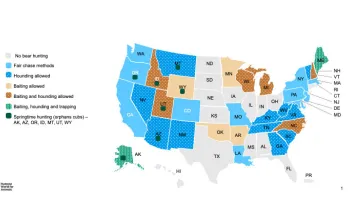

Yet, black bear trophy hunting has increased in popularity in recent years, to an alarming degree. In 2020, hunters killed a record 50,789 black bears in the U.S. Of the 35 U.S. states that permit bear hunting, some allow unethical, inhumane methods, such as using fetid bait piles, hunting with packs of radio-collared hounds, and some western states allow springtime hunts when mothers have dependent—sometimes newborn—cubs with them. In 2024, Louisiana opened a black bear hunt for the first time since the 1980s, and this year, Florida is gunning for a hunt after passing a ballot initiative in 2024 that privileges the interests of hunters over all other citizens.

We also anticipate fighting to protect grizzly bears from trophy hunts in their lower-48 ecosystems near Yellowstone and Glacier national parks, if those bears lose federal protections. And in Alaska, we are working to stop state agents from shooting bears, as well as wolves, from helicopters. These are outrageous practices, and it’s unthinkable that such methods still exist.

At Humane World for Animals, we are determined to end the trophy hunting of bears and to promote nonlethal solutions to wildlife conflicts, some of which involve bears. Together, we can give bears the treatment and protections they deserve.

I am so glad to be a part of these projects, especially since I have witnessed firsthand the beauty and joy that bears like that mother and cubs can bring to the world. Since seeing that bear family, I have returned to Yellowstone several times for bear watching. I’ve met people from all over the world there, all hoping to catch a glimpse of these animals. I spoke before of the magic of seeing these bears, and I think that what is actually magical is that just the vision of these animals can awaken such fascination and joy in human beings. And now, I've become one of those people with ridiculously long lenses.

Wendy Keefover is the senior strategist of native carnivore protection at Humane World for Animals.